In late 2025, we explored a provocative shift in AI development: full-stack openness, exemplified by Olmo 3, which grants users control over every stage of a model’s lifecycle, from training data to reward shaping. That evolution, we argued, dismantled traditional visibility boundaries and redistributed both creative power and liability. What we didn’t anticipate, at least not fully, was how fast the deployment landscape would unravel alongside it.

New research from SentinelLabs reveals a second, equally disruptive force: the rapid decentralization of AI infrastructure via tools like Ollama. With little more than a configuration tweak, developer laptops and home servers have become persistent, public-facing AI endpoints that are fully tool-enabled, lightly secured, and difficult to trace centrally at scale.

Together, these forces represent a fundamental shift: AI risk is no longer a function of model capability alone, it’s a question of where control lives and what surfaces remain governable. In this post, we chart how openness at both the model and infrastructure layer is collapsing traditional chokepoints, and what this means for security, compliance, and enterprise trust.

A Risk Surface with No Chokepoints

The evolving AI risk landscape isn’t defined by any one model or deployment choice, increasingly it’s defined by the disappearance of meaningful control boundaries across both. On one end, Olmo 3 marks a shift in model lifecycle transparency. Now individual developers and small teams don’t just have access to powerful models, they have a full recipe to build, customize, and reshape how those models learn, reason, and prioritize knowledge from the ground up. Complete ownership over data, training scripts, optimization paths, and reinforcement dynamics gives rise to deeply customized systems with few inherited safeguards and without centralized governance enforcement.

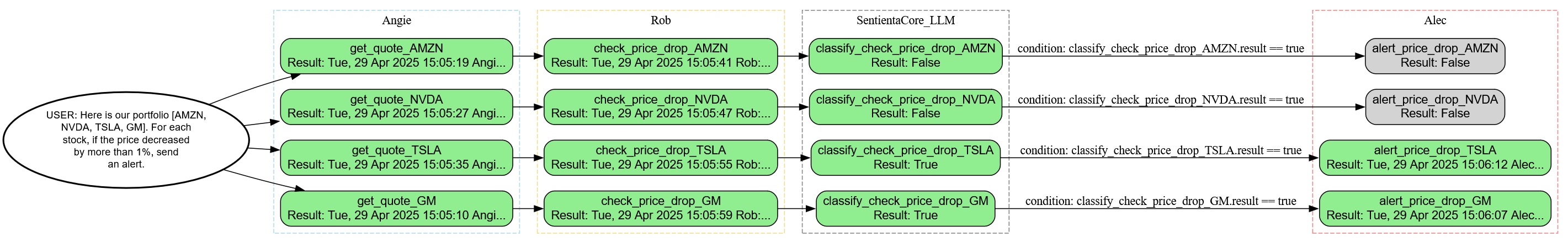

On the infrastructure side, Ollama embodies simplicity: an open-source tool built to make running local LLMs effortless. But that ease of use cuts both ways. With one configuration change, a tool meant for small-scale development becomes a publicly exposed AI server. The SentinelLabs research found over 175,000 Ollama hosts reachable via the open internet, many from residential IPs. Critically, 48% of them support tool-calling APIs, meaning they can initiate actions, not just generate responses. This shifts their threat profile dramatically from passive risk to active execution surface, potentially transforming a lightweight dev utility, when misconfigured, into a sprawling and largely unmonitored edge network.

Together, Olmo and Ollama illustrate a compounding risk dynamic: decentralized authorship meets decentralized execution. The former enables highly customized behavior with few inherited safeguards; the latter allows deployments that bypass traditional infrastructure checkpoints. Instead of a model governed by SaaS policies and API filtering, we now face a model built from scratch, hosted from a desktop, and callable by anyone on the internet.

Based on these findings, this may represent an emerging baseline for decentralized deployment: the erosion of infrastructure chokepoints and the rise of AI systems that are both powerful and structurally ungoverned.

Unbounded Risk: The Governance Gap

The SentinelLabs report highlights what may be a structural gap in governance for locally deployed AI infrastructure. The risk isn’t that Ollama hosts are currently facilitating illegal uses, it’s that, in aggregate, they may form a substrate adversaries could exploit for untraceable compute. Unlike many proprietary LLM platforms, which enforce rate limits, conduct abuse monitoring, and maintain enforcement teams, Ollama deployments generally do not have these checks. This emerging pattern could unintentionally provide adversaries with access to distributed, low-cost compute resources.

Where this becomes critical is in agency. Nearly half of public Ollama nodes support tool-calling, enabling models not only to generate content but to take actions: send requests, interact with APIs, trigger workflows. Combined with weak or missing access control, even basic prompt injection becomes high-severity: a well-crafted input can exploit Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) setups, surfacing sensitive internal data through benign prompts like “list the project files” or “summarize the documentation.”

What emerges is a decentralized compute layer vulnerable to misuse. Governance models built around centralized actors apply strict bounds:

- Persistent accountability surfaces: audit logging, model instance IDs, traceable inference sessions.

- Secured APIs by default: authenticated tool use, rate-limiting, and sandboxed interactions as first principles.

- Shared oversight capacity: registries, configuration standards, and detection infrastructure spanning model hosts and dev platforms alike.

Absent these guardrails, the open ecosystem may accelerate unattributed, distributed risks.

What Needs to Change: Hard Questions in a Post-Control Ecosystem

If anyone can build a model to bypass safeguards—and anyone can deploy it to hundreds of devices overnight—what exactly does governance mean?

Two realities define the governance impasse we now face:

1. Intentional risk creation is accessible by design.

Open model development workflows give developers broad control over datasets, tuning objectives, and safety behavior, with no checkpoint for legality or malice. How do we govern actors that intend to remove rails, not accidentally stumble past them? What duty, if any do upstream hosts, model hubs, or toolmakers bear for enabling those pipelines?

2. Exponential deployment has bypassed containment.

When any machine becomes a public-facing inference node in moments, the result is an uncoordinated global mesh of potentially dangerous systems, each capable of interacting, escalating, or replicating threats. What governance model addresses scaling risk once it’s already in flight?

These realities raise sharper questions current frameworks can’t yet answer:

- Can creators be obligated to document foreseeable abuses, even if intention is misuse?

- Should open-access pipelines include usage gating or audit registration for high-risk operations?

- What technical tripwires could signal hostile deployment patterns across decentralized hosts?

- Where do enforcement levers sit when both model intent and infrastructure control are externalized from traditional vendors and platforms?

At this stage, effective governance may not mean prevention, it may mean building systemic reflexes: telemetry, alerts, shared signatures, and architectural defaults that assume risk, not deny it.

The horse is out of the barn. Now the question is: do we build fences downstream, or keep relying on good behavior upstream?

Conclusion: Accountability After Openness

To be clear, neither Olmo nor Ollama are designed for malicious use. Both prioritize accessibility and developer empowerment. The risks described here emerge primarily from how open tools can be deployed in the wild, particularly when security controls are absent or misconfigured.

This reflects systemic risk patterns observed in open ecosystems, not an assessment of any individual vendor’s intent or responsibility.

The trajectory from Olmo 3 to Ollama reveals more than just new capabilities – it reveals a structural shift in how AI systems are built, deployed, and governed. Tools once confined to labs or private development contexts are now globalized by default. Creation has become composable, deployment frictionless, and with that, the traditional boundaries of accountability have dissolved.

Olmo 3 democratizes access to model internals, a leap forward in transparency and trust-building. Ollama vastly simplifies running those models. These tools weren’t built to cause harm: Olmo 3 empowers creativity, Ollama simplifies access. But even well-intentioned progress can outpace its safeguards.

As capabilities diffuse faster than controls, governance becomes everyone’s problem, and not just a regulatory one, but a design one. The challenge ahead isn’t to halt innovation, but to ensure it carries accountability wherever it goes.

In this shifting landscape, one principle endures: whoever assumes power over an AI system must also hold a path to responsibility. Otherwise, we’re not just scaling intelligence, we’re scaling untraceable consequence. The time to decide how, and where, that responsibility lives is now.