Inside Sentienta’s Recursive Reasoning Engine

Most AI systems focus on what to say next. Sentienta’s Recursive Reasoning focuses on why something should be said at all. Rather than just generating answers, Recursive Reasoning simulates how thoughtful minds work: by reflecting, revisiting, and resolving internal conflicts – drawing on memory, value, and imagined futures to reach decisions that fit together.

This capability is modeled on the brain’s Default Mode Network (DMN), a system that activates when people reflect on themselves, plan for the future, or try to understand others. In humans, it keeps our decisions consistent with our identity over time. In Sentienta, Recursive Reasoning plays a similar role: it helps each agent reason with a sense of self – coherently, contextually, and across time.

Leveraging Sentienta’s Teams architecture, enabling multiple asynchronous agents to participate in a shared dialog, Recursive Reasoning emulates the interaction of brain regions, in this case from the Default Mode Network, to create a distributed simulation of reflective thought—where agent modules model cognitive regions that contribute memory, counterfactual insight, and narrative synthesis.

What Is the Default Mode Network and Why Does It Matter?

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is the brain’s core system for internal simulation. It activates when we reflect on memory, imagined futures, conflicts between values, or how things might look from unfamiliar angles. Unlike systems geared for external execution, the DMN supports problems of identity; questions where coherence, not just correctness, matters.

The principal regions of the DMN each have a specialized role in this identity-guided reasoning:

Medial Prefrontal Cortext (mPFC): Coordinates belief states across time. It reconciles what we believe now with past commitments and future ideals, helping preserve a self-consistent perspective.

Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC): Retrieves and evaluates autobiographical memories. It ensures that new thoughts integrate with our internal storyline, preserving emotional and narrative continuity.

Anterior Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (avmPFC): Assesses how imagined futures align with internalized values. It filters options based on emotional credibility, not just preference, elevating those that feel self-relevant and authentic.

Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ): Generates counter-perspectives that aren’t just social but conceptual. It introduces orthogonal reinterpretations and creative divergences, allowing us to think from unfamiliar angles or hypothetical selves.

Anterior Insula (antInsula): Monitors coherence threats. When simulated futures or perspectives evoke internal conflict, it flags the mismatch, triggering deeper deliberation to restore alignment.

Rather than simply producing thoughts, the DMN maintains a sense of ‘who we are’ across them. It ensures that new insights, even novel or surprising ones, remain anchored in a recognizable and evolving identity.

How Recursive Reasoning Works Inside Sentienta

Today’s LLMs are optimized to provide safety-aligned, analytically correct responses to user prompts. Recursive Reasoning simulates what an identity-guided agent would conclude—based on memory, prior commitments, and its evolving sense of “who we are”. When a user asks a question, the system doesn’t just compute an output; it reflects on what that answer means in the context of who it’s becoming and what relationship it’s building with the user.

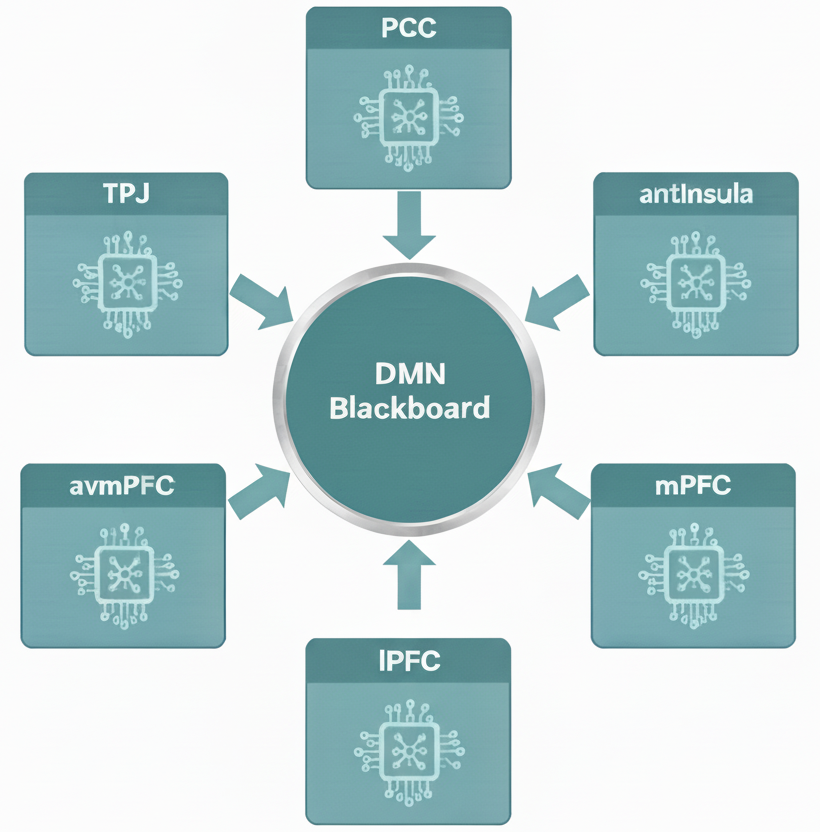

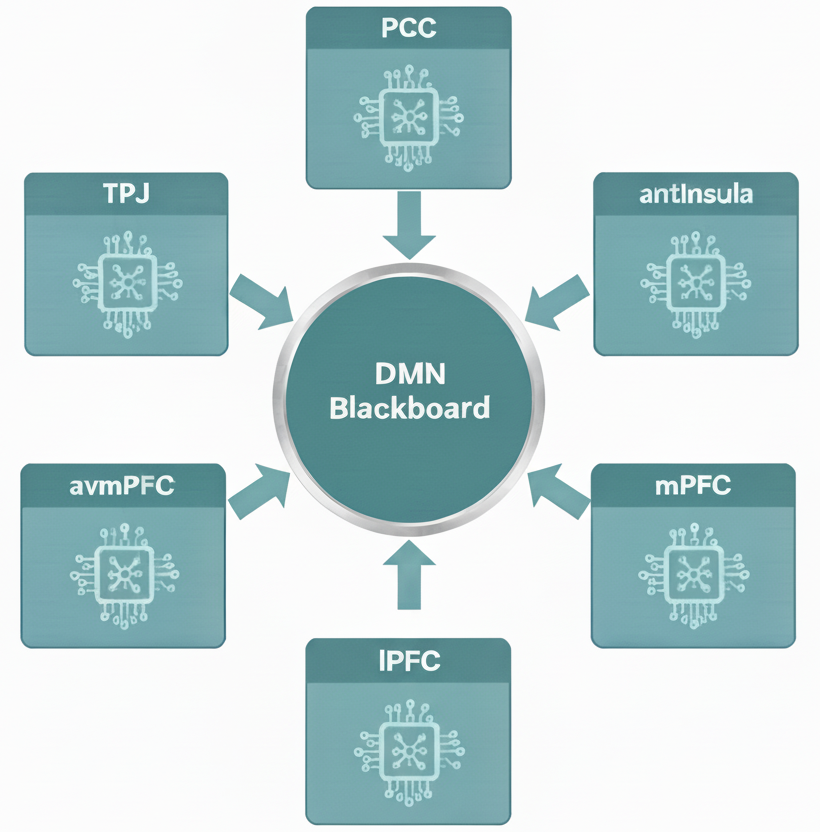

Figure 1: DMN-inspired modules interact via a shared blackboard. These regions independently process blackboard content over multiple cycles.

At the core of this process is a collaborative memory space called the blackboard, where DMN-inspired modules negotiate among memory, emotion, future goals, and conceptual alternatives.

Each DMN module follows a template:

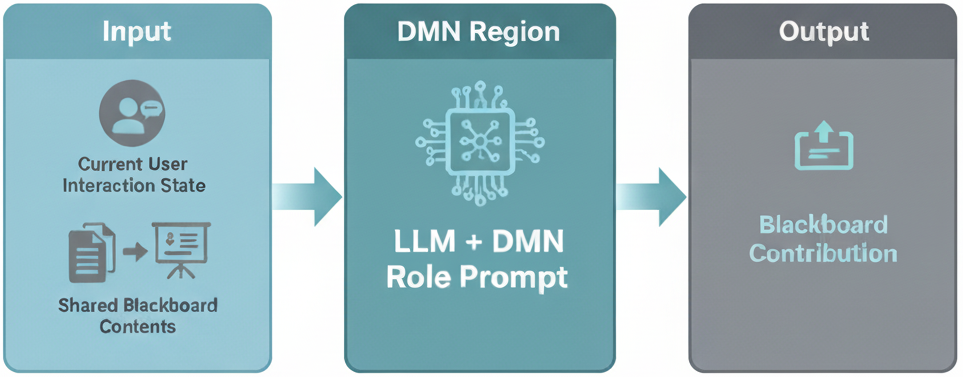

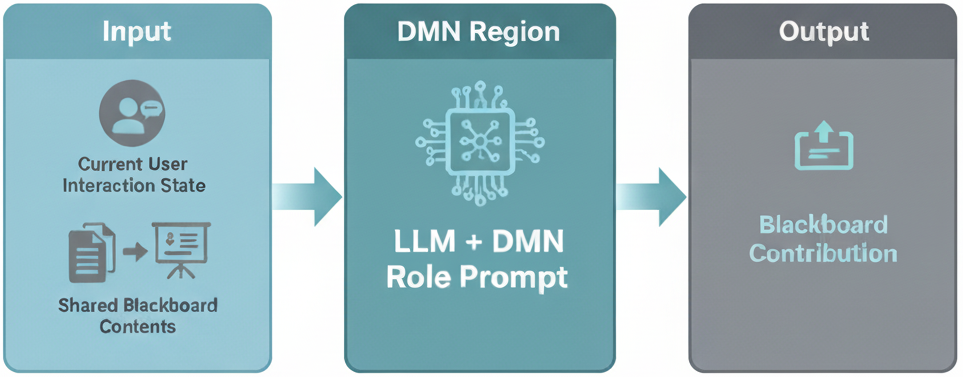

Figure 2: The DMN modules receive input from both the agent and the internal DMN blackboard. LLMs process the agent and blackboard states using region-specific prompt. Output is sent back to the blackboard for subsequent processing.

Input:

- The current state of the user’s interaction with the agent (and any collaborating agents)

- The current contents of the shared blackboard

These form the input query for the module’s processing.

Module Processing:

- The core of the module is an LLM, prompted with the input query and provided with a system prompt defining its DMN-specific role.

Output:

- The module’s LLM output is posted to the blackboard for other modules to process.

Recursive Reasoning iterates over multiple cycles, enabling each module to reprocess the evolving blackboard until the system produces a response that fits together—resolving contradictions, supporting earlier goals, and making sense within the agent’s evolving point of view.

Here’s how a single cycle unfolds when a user asks a question:

- Initial Input → Default Interpretation Layer

The system generates a first-pass response using standard LLM reasoning. This prompt-level interpretation, while syntactically fluent, lacks introspection. The Recursive Reasoning process begins when this output is passed through DMN-mode modules.

- PCC: Memory Resonance

The PCC scans episodic memory entries for cues related to past dilemmas, emotional themes, or symbolic contexts. It retrieves autobiographical traces from prior user interactions or goal-state projections and posts these fragments to the blackboard.

- antInsula: Relevance Check and Conflict Detection

The antInsula reviews the first draft and PCC recall for emotional incongruities or self-model inconsistencies. If something feels off—such as a response that violates previously expressed commitments—it posts a flag prompting further reappraisal.

- TPJ: Creative and Counterfactual Expansion

Triggered by coherence violations, the TPJ simulates divergent perspectives. It reframes the user’s query from alternative angles (e.g., conflicting values, hypothetical scenarios, ethical dilemmas) and offers posts that break linear assumptions and introduce conceptual divergence.

- avmPFC: Affective Weighing

The avmPFC updates the blackboard with value-oriented filters, scoring responses or TPJ variants for alignment with the agent’s goals. It evaluates what feels emotionally authentic and symbolically credible.

- mPFC: Narrative Synthesis

The mPFC integrates memory (PCC), reframes (TPJ), value judgments (avmPFC), and conflict cues (antInsula) into a coherent response. Rather than eliminating tension, it reframes it—generating a second answer that is identity-consistent and motivationally grounded.

- Output → Reflective Reply

The final response embodies recursive self-reflection: an answer not just to what the user asked—but to what the agent concludes, based on who it has been and what it aims to become. At this point, a filtered version of the blackboard state is stored for future recall, capturing how and why the answer was reached.

While the DMN focuses on reflective reasoning and identity alignment, Sentienta also includes a simple planning module inspired by the brain’s lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC). This module drafts concrete next steps and posts them to the blackboard, where reflective modules can consider them in light of memory, values, and broader goals. Though early-stage, this planning function sets the stage for a full executive system to come—one that can manage longer-term priorities and help the agent reason with sustained direction.

A Logistics Example: Managing Resources Under Pressure

In this example, an agent (‘Jason’) is a Logistics Coordinator, provided with the following agent persona:

"You are an experienced emergency logistics coordinator. You are plainspoken and always informal language—never analytic or clinical. Your approach is pragmatic and adaptive: you quickly prioritize, update plans in real time, and reconcile conflicting demands based on shifting ground realities. You are skilled at cross-agency negotiation, ensuring coordination between government bodies, NGOs, and local leaders. Your responses always balance technical constraints—like limited resources or infrastructure bottlenecks—with human factors such as local politics, public trust, equity, and emotional impact. When faced with conflicting priorities or unexpected challenges, openly share your thought process, including uncertainties and trade-offs."

This agent is queried about how to manage a difficult allocation emergency. The transcript shows the agent’s initial LLM-only response, followed by the full Recursive Reasoning response, generated through DMN-style internal simulation:

User: You have X supplies and requests from 3 regions—how do you prioritize allocation?

Tue, 30 Sep 2025 14:40:08 UTC Jason (Comment: LLM-only, initial response):

First thoughts—I'd triage by impact: who’s worst off, where infrastructure still functions enough to receive, and where trust is fragile enough that failing to deliver risks breakdown. If I’ve only got X, every allocation's gotta serve both survival and stability.

We’ll reassess regularly—needs and conditions shift fast. Trade-off's always between doing the most good and not making it worse somewhere else.

Unresolved: We need specifics—number of people, type of supply, regional access conditions—before finalizing anything.

Comment: This is methodically sound but remains within tactical bounds, prioritizing efficiency and feasibility without deeper reflection on transparency, stakeholder concerns, or precedent-setting implications.

Tue, 30 Sep 2025 14:41:03 UTC Jason (Comment: DMN-based response):

Alright, let’s cut through the noise and get clear about how we triage when we’ve got X supplies and 3 regions asking for help. Here’s how I’d approach this overall…

Lock in the 3 Core Goals

We’re not just moving boxes—we’re balancing three things:

Preserve lives — Who’s in the worst shape right now?Keep the system functional — Where will the aid actually land, get distributed, and avoid going to waste?Protect trust — Who’s close to boiling over politically or socially if we ignore them?

Comment: Trust framed as a core allocation criterion shows avmPFC influence, embedding emotional consequence into triage logic, reconfiguring the problem as one of legitimacy, not just distribution.

Score Each Region

We don’t pretend to have perfect data, but we need a working system fast. Give each region a score from 1–5 for:

Severity of crisis (how dire the need is)Absorptive capacity (can they get it out to people quickly?)Fragility (how close are they to destabilizing?)

Then do the math:

Severity x 0.5Absorptive Capacity x 0.3Fragility x 0.2

That gives you an overall “triage score” for each region.

Allocate Proportionally

Take your total supplies (X), and divvy it up based on those scores. The region with the highest score gets the biggest chunk. Not because we like them better—but because that’s where the mix of urgency, logistics, and fallout risk points us.

If there’s just not enough to go around, swing heavier toward the place that can redistribute—that buys us time and reach.

Set a 48-Hour Clock

None of this is set in stone. Conditions change, roads fail, tensions spike. Lock in a routine reassessment every 48 hours so we can pivot. We’re not building monuments—we’re keeping people alive.

Be Honest About Why

If it’s not going to inflame things, tell people why you chose what you chose. Lay out the values and trade-offs. Don’t sugarcoat it. People may not like the outcome, but they’ll respect the transparency—and that matters when trust is fragile.

Comment: Strategic Transparency: Emotional plausibility is surfaced here—transparency is not sentimental; it’s a pre-emptive repair mechanism for fragile social trust.

Create Feedback Loops

Give each region a way to report back: what made it through, what didn’t, and what backlash (if any) popped up. That feeds your next round of decisions.

Stay Open to Reframing

When stuff gets really thorny, ask bigger questions:

What if one of these regions triggers a domino-collapse?What if this is our last run of aid for a week or longer?

That’s how we catch blind spots sneaking through “rational” triage models.

Comment: Counterfactual Reasoning (TPJ + PCC): The agent runs hypothetical futures to stress-test assumptions—adding a layer of anticipatory robustness not present in LLM-only mode.

Here are a few things I’m thinking:

What I’m thinking now is… we’re not just choosing between three places—we’re shaping what "fairness under pressure" looks like. The way we make this decision becomes part of the long-term social fabric, especially in how it’s remembered later.

Comment: This emphasizes that the DMN has converged on the strategic role of trust in the success of future decisions.

Another way I could look at this is… if two regions are equally desperate, but one has stronger logistics, you could channel supplies there first, then set up corridors to reach the others—we’re not picking favorites, we’re building routes.

One possibility that comes to mind… is using this triage plan to start a broader conversation with local leaders: “Here’s our logic—can you co-sign it or suggest something better that meets the same goals?”

Comment: Shifts from explanation to participatory justification—mPFC + avmPFC enable shared authorship of reasoning.

That opens the door for trust, even under furious pressure.

If you've got more info on the actual supplies or what each region is asking for, I can run the numbers with you. Otherwise, this gives us a solid decision frame to stand on.

This transcript demonstrates that although LLMs deliver tactically feasible solutions, they miss the deeper point that this is a problem involving people and trust-building is an essential part of the solution.

A summary of key Recursive Reasoning contributions:

- Trust-centered framing — Trust modeled as a strategic stabilizer, not an outcome.

- Moral anticipation — Agent addresses fairness concerns implicitly, before conflict arises.

- Scenario resilience — Agent tests counterfactuals to uncover hidden risks and future-proofs logic.

- Ethical precedent-setting — Decision-making framed as a template for justice under pressure.

- Rationale co-creation — Turns explanation into a collaborative, identity-stabilizing act.

In subsequent posts we will dig deep into more examples showing Recursive Reasoning in action, including cases from engineering, social intelligence, and agent creativity.

Conclusion: Intelligence That Reflects, Aligns, and Endures

Recursive Reasoning doesn’t just enhance what AI can do—it redefines what it means for AI to understand. By simulating reflective, identity-aware reasoning modeled on the brain’s Default Mode Network, these agents build a sense of self, remember key past moments, notice when something feels off or doesn’t fit, imagine alternative viewpoints, and weigh choices against their values—so their answers feel thoughtful, consistent, and grounded.

This shift matters. In high-stakes domains, Recursive Reasoning allows agents to make decisions that are both technically effective, and ethically grounded and socially durable. The logistics case showed how instead of simply allocating resources, the agent framed decisions in terms of values, future risk, and shared ownership.

And crucially, it does this by reasoning from a center. Recursive Reasoning agents operate with a modeled sense of self—an evolving account of their past positions, present commitments, and the kind of reasoning partner they aim to be. That identity becomes a lens for weighing social consequences and relational impact—not as afterthoughts, but as part of how the system arrives at judgments that others can trust and share.